Factors for effective powder moistening in the mixing process

In many industries, bulk materials are routinely wetted with a wide variety of liquids. At first glance, wetting a solid surface with a liquid seems trivial, such as when rain hits the ground or a heated forged part is quenched in water. However, wetting powdered solids is much more complex:

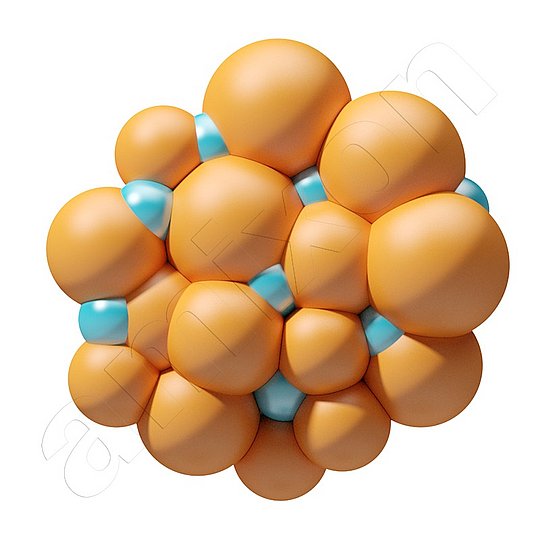

- Powders have a very large specific surface area.

- They have pronounced capillary structures.

- In addition, they have different (heterogeneous) particle surfaces.

These factors determine the wetting speed and penetration into the pores. In practice, this often leads to undesirable effects:

- Undesirable agglomerates or lumps form

- The liquid does not distribute homogeneously throughout the particle collective

- The moistened powder has poor flow properties

- Adhesions occur in the mixer, disrupting the process

Such problems can usually be solved well with amixon® mixers. In more difficult cases, however, it can still be helpful to keep some physical relationships in mind.

Powder moistening can lead to unwanted contamination of the mixer

Depending on the viscosity and adhesion tendency of the liquid, deposits may form on the walls and mixing tools. A high filling level in the mixing chamber counteracts this, as the dry powder serves as an absorbent medium. It is advantageous to spray the liquid into the lower part of the mixing chamber.

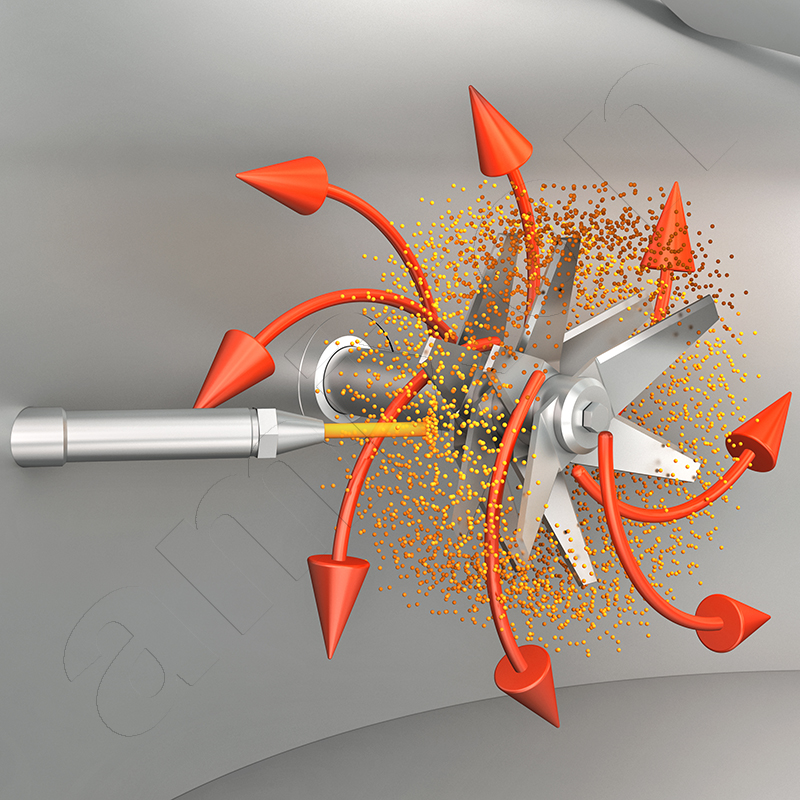

The type of liquid input is crucial for preventing deposits. High concentration gradients should be avoided. For this reason, amixon® uses spray lances with suitable nozzles. The volume flow of the liquid depends on the adsorption capacity of the powder and the mixing intensity. A higher relative velocity between the droplets and the particle stream promotes fine dispersion. This effect can be described by the Weber number.

We = ρ v² d / γ

ρ … density of the liquid

v … relative velocity of the droplets to the powder

d … characteristic droplet diameter

γ … surface tension

The Weber number relates the inertial forces of a droplet to the stabilising surface forces. High values favour the fragmentation of the droplets and thus a more even distribution in the powder. Low values, on the other hand, favour large droplets that tend to stick to the wall surfaces or mixing tools.

Adhesions in the mixer are undesirable. They can distort the mixing result. In addition, adhesions tend to multiply from batch to batch and, on occasion, detach uncontrollably. Adhesions increase friction in the mixing process, generate local heating and, in extreme cases, can block the tools. The optimal method of liquid injection can be determined under realistic conditions at the amixon® technical centre.

Depending on the viscosity and adhesion tendency of the liquid, deposits may form on the walls and mixing tools. A high filling level in the mixing chamber counteracts this, as the dry powder serves as an absorbent medium. It is advantageous to spray the liquid into the lower part of the mixing chamber.

The type of liquid input is crucial for preventing deposits. High concentration gradients should be avoided. For this reason, amixon® uses spray lances with suitable nozzles. The volume flow of the liquid depends on the adsorption capacity of the powder and the mixing intensity. A higher relative velocity between the droplets and the particle stream promotes fine dispersion. This effect can be described by the Weber number.

We = ρ v² d / γ

ρ … density of the liquid

v … relative velocity of the droplets to the powder

d … characteristic droplet diameter

γ … surface tension

The Weber number relates the inertial forces of a droplet to the stabilising surface forces. High values favour the fragmentation of the droplets and thus a more even distribution in the powder. Low values, on the other hand, favour large droplets that tend to stick to the wall surfaces or mixing tools.

Adhesions in the mixer are undesirable. They can distort the mixing result. In addition, adhesions tend to multiply from batch to batch and, on occasion, detach uncontrollably. Adhesions increase friction in the mixing process, generate local heating and, in extreme cases, can block the tools. The optimal method of liquid injection can be determined under realistic conditions at the amixon® technical centre.

How liquid-affine is the powder surface? What is the capillarity of the powder?

The affinity of a powder towards a liquid is determined by the surface energy of its particles and its capillary structure. Both variables control how easily the liquid advances or recedes. A suitable physical measure for this is capillary pressure. It describes the force with which a liquid is drawn into the pores and interstices of the powder.

Δp = (2 γ cos θ) / r

Δp is the capillary pressure.

γ denotes the surface tension of the liquid.

θ is the contact angle between the liquid and the powder surface.

r is the effective capillary radius in the powder.

High surface tension and a small contact angle produce high capillary pressure. This causes the liquid to be sucked quickly and deeply into the pores of the particles. Large contact angles, on the other hand, significantly reduce capillary pressure. In this case, the liquid remains mainly on the particle surface. Small capillary radii increase the ‘suction effect’ of the capillary.

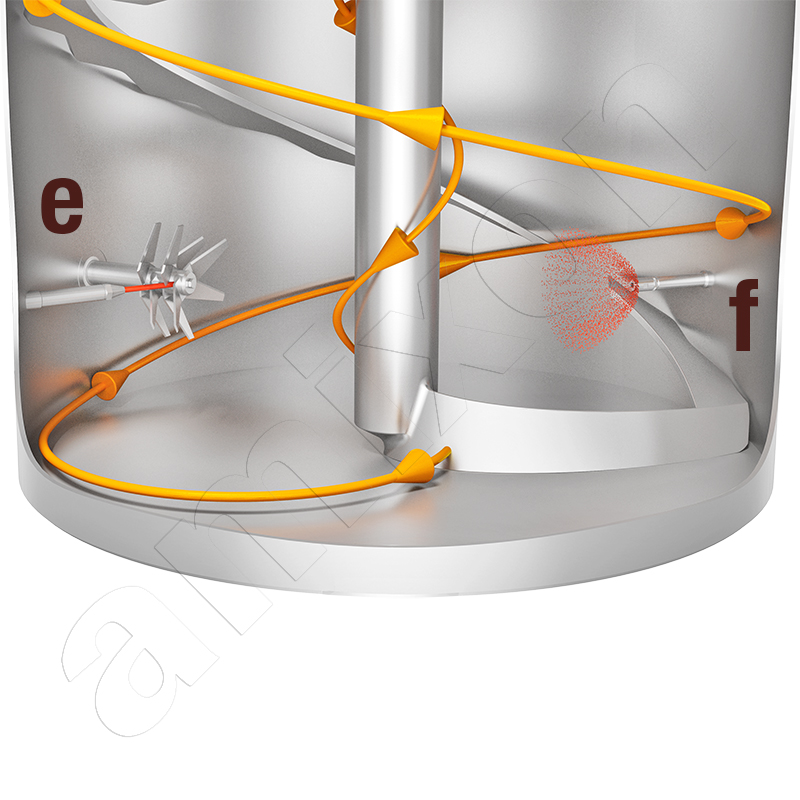

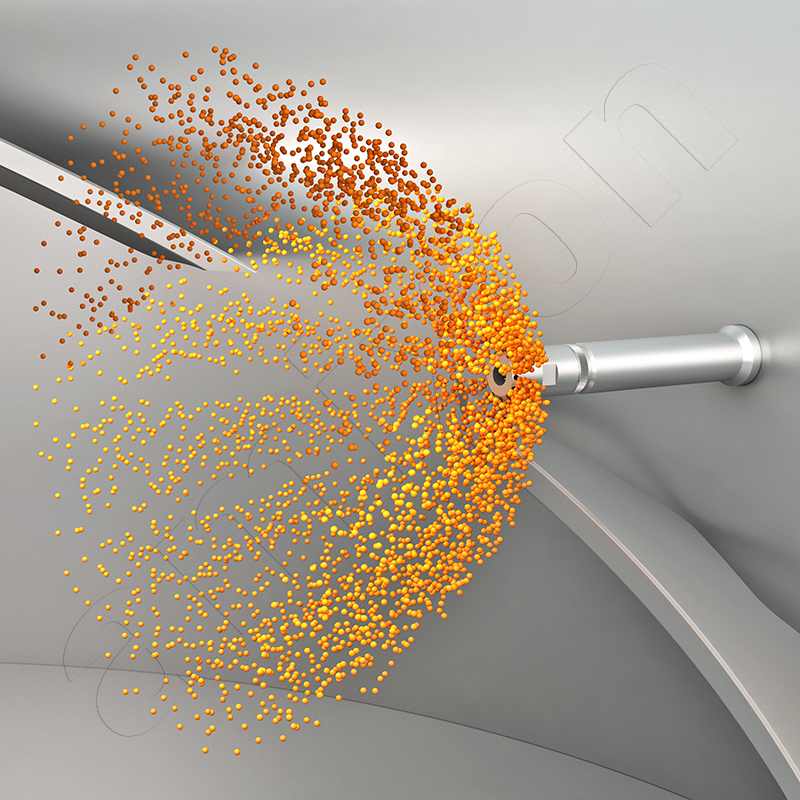

Explanations of the image:

a) Low surface tension, b) High surface tension, c) Refluxing liquid, d) Advancing liquid, e) Liquid is injected into the turbulence zone of the swirler (single-substance nozzle), f) Liquid is sprayed in microfine droplets and the powder is fluidised (two-component nozzle)

The affinity of a powder towards a liquid is determined by the surface energy of its particles and its capillary structure. Both variables control how easily the liquid advances or recedes. A suitable physical measure for this is capillary pressure. It describes the force with which a liquid is drawn into the pores and interstices of the powder.

Δp = (2 γ cos θ) / r

Δp is the capillary pressure.

γ denotes the surface tension of the liquid.

θ is the contact angle between the liquid and the powder surface.

r is the effective capillary radius in the powder.

High surface tension and a small contact angle produce high capillary pressure. This causes the liquid to be sucked quickly and deeply into the pores of the particles. Large contact angles, on the other hand, significantly reduce capillary pressure. In this case, the liquid remains mainly on the particle surface. Small capillary radii increase the ‘suction effect’ of the capillary.

Explanations of the image:

a) Low surface tension, b) High surface tension, c) Refluxing liquid, d) Advancing liquid, e) Liquid is injected into the turbulence zone of the swirler (single-substance nozzle), f) Liquid is sprayed in microfine droplets and the powder is fluidised (two-component nozzle)

Capillarity of the powder and surface tension of the liquid

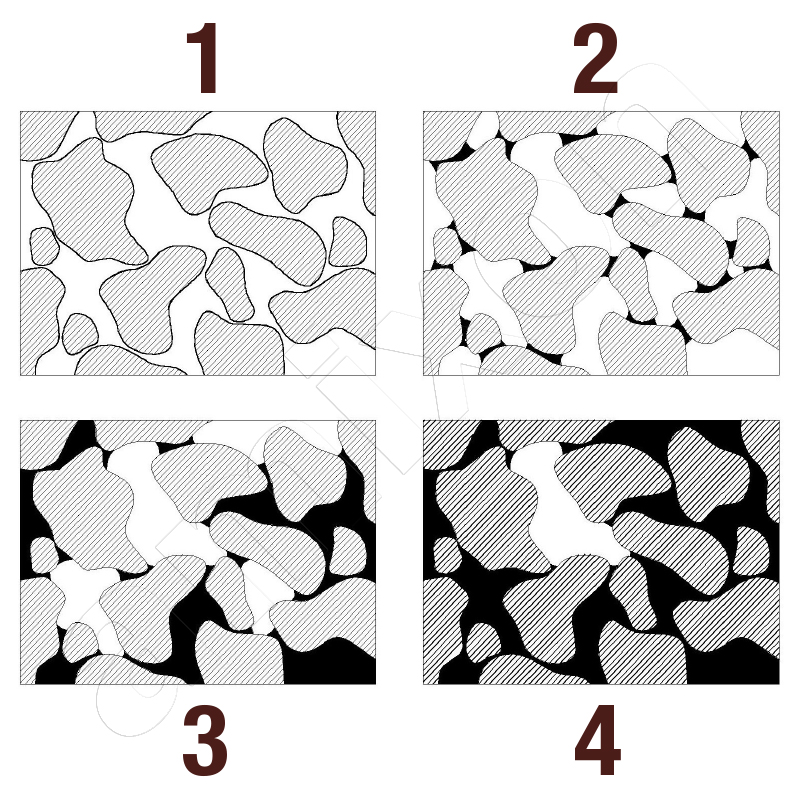

The capillary structure of the powder and the surface tension of the liquid influence how easily it penetrates the pores of the particles. At low surface tension, the liquid spontaneously wets the particle surface. It also penetrates fine capillaries. With high surface tension, however, the capillary pressure is low. The liquid remains on the surface and does not fill the pores sufficiently.

This applies to both individual particles and the cavities of a particle collective. In this case, uniform liquid distribution is therefore only possible if the powder is mixed intensively. The particles must be rubbed together intensively.

The capillary structure of the powder and the surface tension of the liquid influence how easily it penetrates the pores of the particles. At low surface tension, the liquid spontaneously wets the particle surface. It also penetrates fine capillaries. With high surface tension, however, the capillary pressure is low. The liquid remains on the surface and does not fill the pores sufficiently.

This applies to both individual particles and the cavities of a particle collective. In this case, uniform liquid distribution is therefore only possible if the powder is mixed intensively. The particles must be rubbed together intensively.

The homogeneous wetting of a powder is not trivial

In the dry state, the particles are close together. There is air between them. These cavities change constantly during mixing. When a liquid is added, the air must be displaced from the pores. Initially, the liquid forms a thin adsorption layer around the particles. This layer usually adheres firmly and can only be removed by evaporation.

As the liquid content increases, capillary bridges form at the contact points. This allows the particles to bond together. This is how build-up granulation begins. Further addition of liquid fills larger cavities. Once all the capillaries are filled, the powder is saturated. It then turns into a suspension. The penetration of the liquid into the capillaries can be described using the Washburn equation.

L² = γ * r * t * cos(θ) / (2 * η)

L is the penetration depth

γ is the surface tension

θ is the contact angle

η is the viscosity

r is the capillary radius

t is the time.

A small contact angle and low viscosity promote penetration. High viscosity or hydrophobic surfaces, on the other hand, inhibit it. Wettability depends on the microstructure of the particles. Roughness changes the apparent contact angle. This is described by the Wenzel relationship:

cos(θW) = rf * cos(θ)

θW is the apparent contact angle on a rough surface

rf is the roughness factor.

Heterogeneous surfaces behave differently. The Cassie-Baxter equation applies here:

cos(θCB) = f₁ * cos(θ₁) + f₂ * cos(θ₂)

θCB is the apparent contact angle on a mixed surface f₁ and f₂ are the surface areas of different surface types

θCB is the apparent contact angle on a mixed surface

f₁ and f₂ are the surface areas of different surface types

At low surface tension and high affinity, so-called flash absorption can occur. This means that the available liquid is absorbed immediately and completely. This can have a negative effect on the mixing quality. In such cases, the liquid should therefore be sprayed more slowly and particularly finely. If the addition is made below the bulk material level, condensation in the mixing chamber is also avoided. Mixing tools and mixing chamber remain clean. Every gram of liquid is distributed in the powder without loss.

In the dry state, the particles are close together. There is air between them. These cavities change constantly during mixing. When a liquid is added, the air must be displaced from the pores. Initially, the liquid forms a thin adsorption layer around the particles. This layer usually adheres firmly and can only be removed by evaporation.

As the liquid content increases, capillary bridges form at the contact points. This allows the particles to bond together. This is how build-up granulation begins. Further addition of liquid fills larger cavities. Once all the capillaries are filled, the powder is saturated. It then turns into a suspension. The penetration of the liquid into the capillaries can be described using the Washburn equation.

L² = γ * r * t * cos(θ) / (2 * η)

L is the penetration depth

γ is the surface tension

θ is the contact angle

η is the viscosity

r is the capillary radius

t is the time.

A small contact angle and low viscosity promote penetration. High viscosity or hydrophobic surfaces, on the other hand, inhibit it. Wettability depends on the microstructure of the particles. Roughness changes the apparent contact angle. This is described by the Wenzel relationship:

cos(θW) = rf * cos(θ)

θW is the apparent contact angle on a rough surface

rf is the roughness factor.

Heterogeneous surfaces behave differently. The Cassie-Baxter equation applies here:

cos(θCB) = f₁ * cos(θ₁) + f₂ * cos(θ₂)

θCB is the apparent contact angle on a mixed surface f₁ and f₂ are the surface areas of different surface types

θCB is the apparent contact angle on a mixed surface

f₁ and f₂ are the surface areas of different surface types

At low surface tension and high affinity, so-called flash absorption can occur. This means that the available liquid is absorbed immediately and completely. This can have a negative effect on the mixing quality. In such cases, the liquid should therefore be sprayed more slowly and particularly finely. If the addition is made below the bulk material level, condensation in the mixing chamber is also avoided. Mixing tools and mixing chamber remain clean. Every gram of liquid is distributed in the powder without loss.

Physical background of adhesion and film formation

Unfortunately, many material parameters are not available in practice. Determining them experimentally is costly. Nevertheless, it is helpful to know the Marangoni convection equation. In this equation, liquid films move when their surface tension changes locally. Even small differences in temperature or concentration can trigger film formation.

Ma = ((dγ/dT) * L * ΔT) / (μ * α)

Ma is the Marangoni number

γ is the surface tension

ΔT is the temperature difference

µ is the dynamic viscosity

α is the thermal diffusivity

L is the characteristic length

The tendency to adhere increases in particular when local temperature or concentration differences develop during wetting. It is not the absolute temperature level that is decisive, but the extent of the gradients. Cooled mixing processes therefore have a stabilising effect because they keep the viscosity high and minimise Marangoni currents. High Ma values lead to unstable liquid films.

Another relevant mechanism is the adhesion of thin liquid films. Here, the Johnson-Kendall-Roberts model describes the adhesive force between two particles.

F = (3/2) * π * R * W

F is the adhesive force

R is the effective radius of curvature of the particles

W is the specific adhesion work

High W values promote the formation of solid adhesions. Drops then adhere particularly strongly to mixing tools or walls.

It is best to avoid high concentration gradients. amixon® therefore often uses two- and three-substance nozzles. These can be operated in the middle of the powder bed. They fluidise the powder in the mouth area and atomise the liquid to a microfine level. This means that the free liquid is immediately absorbed by the particles. Adhesions are avoided.

It is particularly advantageous if the powder does not heat up during the mixing process. amixon® mixers support this, as they work with a gentle and energy-efficient mixing mechanism that generates only low shear and friction effects.

Unfortunately, many material parameters are not available in practice. Determining them experimentally is costly. Nevertheless, it is helpful to know the Marangoni convection equation. In this equation, liquid films move when their surface tension changes locally. Even small differences in temperature or concentration can trigger film formation.

Ma = ((dγ/dT) * L * ΔT) / (μ * α)

Ma is the Marangoni number

γ is the surface tension

ΔT is the temperature difference

µ is the dynamic viscosity

α is the thermal diffusivity

L is the characteristic length

The tendency to adhere increases in particular when local temperature or concentration differences develop during wetting. It is not the absolute temperature level that is decisive, but the extent of the gradients. Cooled mixing processes therefore have a stabilising effect because they keep the viscosity high and minimise Marangoni currents. High Ma values lead to unstable liquid films.

Another relevant mechanism is the adhesion of thin liquid films. Here, the Johnson-Kendall-Roberts model describes the adhesive force between two particles.

F = (3/2) * π * R * W

F is the adhesive force

R is the effective radius of curvature of the particles

W is the specific adhesion work

High W values promote the formation of solid adhesions. Drops then adhere particularly strongly to mixing tools or walls.

It is best to avoid high concentration gradients. amixon® therefore often uses two- and three-substance nozzles. These can be operated in the middle of the powder bed. They fluidise the powder in the mouth area and atomise the liquid to a microfine level. This means that the free liquid is immediately absorbed by the particles. Adhesions are avoided.

It is particularly advantageous if the powder does not heat up during the mixing process. amixon® mixers support this, as they work with a gentle and energy-efficient mixing mechanism that generates only low shear and friction effects.

Are practical tests in the mixer still relevant today?

Yes, because although we can now characterise powders and liquids precisely, powder mixtures and wetting processes remain complex. Disperse systems are sensitive to fluctuations in raw material components. While liquid mixing processes can now be simulated well, this is rarely possible with disperse systems.

Mixing tests also reveal unexpected effects in practice. Multi-step processes are particularly interesting, for example, in the preparation of spice mixtures, instant beverages or dietary foods.

At the amixon® technical centre, we carry out a wide variety of wetting processes on an almost daily basis. Using your original products, we will be happy to show you how your powders behave, what they look like, how they flow and whether they adhere. Practical tests provide reliable results that can also be used for robust projections. They therefore remain indispensable.

Yes, because although we can now characterise powders and liquids precisely, powder mixtures and wetting processes remain complex. Disperse systems are sensitive to fluctuations in raw material components. While liquid mixing processes can now be simulated well, this is rarely possible with disperse systems.

Mixing tests also reveal unexpected effects in practice. Multi-step processes are particularly interesting, for example, in the preparation of spice mixtures, instant beverages or dietary foods.

At the amixon® technical centre, we carry out a wide variety of wetting processes on an almost daily basis. Using your original products, we will be happy to show you how your powders behave, what they look like, how they flow and whether they adhere. Practical tests provide reliable results that can also be used for robust projections. They therefore remain indispensable.

© Copyright by amixon GmbH