Nanocomposites

Nanocomposites are composite materials in which at least one phase is present at the nanoscale. Typically, these are nanoparticles, nanofibres or nanoplatelets distributed in a continuous matrix. The matrix can be polymeric, metallic or ceramic. The nanoscale proportion is usually less than a few percent by volume, but has a disproportionately strong influence on the material properties.

The exceptional properties of nanocomposites are primarily due to the large interface between the matrix and the nanoscale phase. Mechanical, thermal, electrical or barrier effects are not caused by the material itself, but by its homogeneous distribution and the quality of the interfaces.

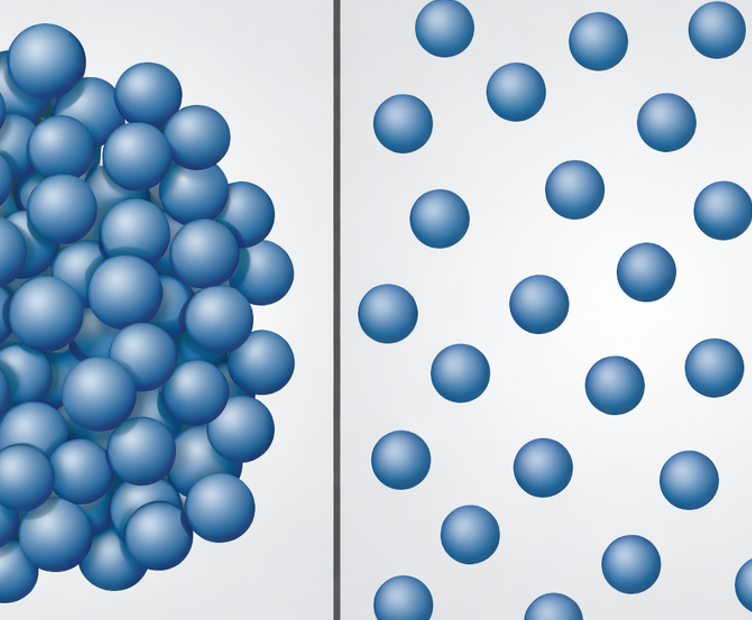

This puts mixing at the centre of materials development. The central process bottleneck is not the mixing of different components, but the complete deagglomeration of the nanoparticles and their stable embedding in the matrix.

Nanoparticles are almost always present as agglomerates in their initial state. These agglomerates are formed during particle synthesis or storage. Their internal binding energy is high because they are stabilised by Van der Waals forces, electrostatic effects or sintering bridges. To produce high-performance nanocomposites, these agglomerates must be completely or at least largely broken up.

The deagglomeration work required for this is closely linked to surface energy. The minimum energy required for separation can be approximated by the formula:

E ≈ γ · ΔA

Here, γ is the specific surface energy and ΔA is the newly created surface area. Since ΔA is extremely large for nanoparticles, the energy required for true primary particle dispersion increases significantly. The decisive factor here is not the total energy, but the locally effective energy density in the mixing process.

For nanocomposites, this means that classic, gravity-dominated mixing mechanisms are not sufficient. Only processes that generate high local shear, compressive stresses or impact energies are effective. Examples include intense shear flows, solid-solid contacts under pressure or the targeted application of shear gradients to wall surfaces.

The wetting of the nanoparticles by the matrix is of great importance. Incomplete wetting stabilises agglomerates and prevents force and charge transfer across the interface. Wettability is determined by the surface chemistry of the nanoparticles, the polarity of the matrix and the process conditions. In many cases, surface modification or the use of dispersing aids is necessary.

From a mixing technology perspective, the sequence of process steps is crucial. Dry premixing is often useful as it breaks up agglomerates and produces a kind of homogeneous premix.

This applies to polymer nanocomposites as well as ceramic and metallic systems. In polymer-based nanocomposites, the viscosity of the matrix also influences the dispersion process. As viscosity increases, shear transfer increases, but at the same time, deaeration becomes more difficult. Trapped air acts as an additional interface and can promote re-agglomeration. Controlled process management, often under vacuum, is therefore an essential quality criterion.

The properties of a nanocomposite depend heavily on the dispersion quality. Even small amounts of agglomerate residue can act as defects in the workpiece.