Surface enlargement

In the context of bulk materials and powders, surface enlargement refers to the comminution of solids. Comminution converts a coarse solid into a large number of smaller particles. As the particle size decreases, the specific surface area, i.e. the freely accessible surface area relative to the mass of the solid, increases.

Comminution can be carried out dry or wet. Dry grinding is carried out without a liquid medium. In wet grinding, the particles are suspended in a liquid. The choice of comminution process depends on the material, the desired fineness and the process-related boundary conditions.

Numerous types of machines are available for comminuting solids.

These include lump crushers, impact crushers, roller mills, friction crushers, hammer mills, air jet mills, ball mills, stirred ball mills, vibrating mills, pin mills, cutting mills, disc mills, planetary ball mills, deagglomerators and classifier mills. The processes differ in the type of force applied, such as pressure, impact, impact, shearing or friction.

A special form of solid material crushing is condensation. In this process, vapours or aerosols from molten metals are rapidly cooled to form solid nanoparticles. The spraying of molten metals, for example by gas atomisation, is another method of increasing surface area. Such processes are used to produce metallic powders with a defined particle size. Another method is pyrolysis, which is used to produce nanostructured black pigments.

The geometry of the resulting particles depends on both the starting material and the grinding mechanism. Particles can be approximately spherical. They can be irregular, angular, sharp or splinter-like. Crystalline solids often exhibit faceted, crystal-like shapes. These properties influence the flow behaviour, bulk density, miscibility and reactivity of a powder.

The increase in surface area means that a solid becomes more effective as the particle size decreases. This can be demonstrated particularly clearly with colour pigments. Very small quantities of finely ground pigments are sufficient to intensively colour large quantities of powders, plastics or textiles. The colour effect depends directly on the freely accessible surface area of the pigment particles.

As the fineness increases, so do the adhesive forces between the particles. Very fine powders therefore have a strong tendency to agglomerate. Nano-fine, dry ceramic powder from high-performance and engineering ceramics can behave in a similarly sticky manner to a coarser powder that has been moistened beforehand. As soon as such particles move relative to each other, agglomerates form. If these consist of nano-fine primary particles, they can exhibit very high mechanical strength.

Such agglomerates can be effectively deagglomerated in high-performance mixers from amixon®, especially when nanopowders need to be mixed homogeneously with other powder components at the same time. Alternatively, deagglomeration is also possible in grinding plants, for example in air jet mills.

The relationship between comminution and surface enlargement can be illustrated geometrically. The starting point is a regularly shaped cuboid with an edge length L. Its volume is L³, its surface area 6·L². If the cuboid is halved in all three spatial directions in a comminution step, eight cuboids of equal size with an edge length L/2 are created.

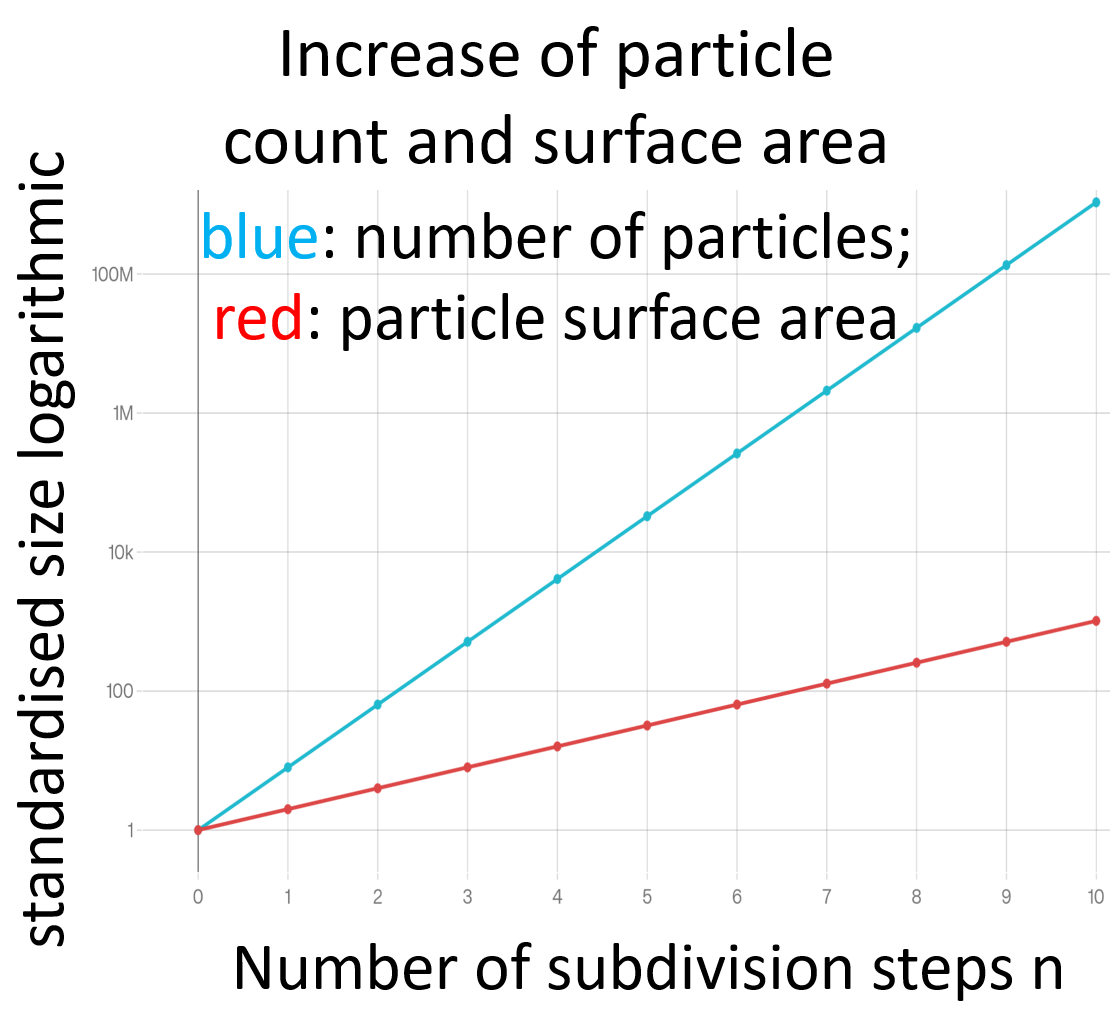

After n grinding steps, the number of particles is

N(n) = 8ⁿ

The surface area of a single particle is

A₁(n) = 6·(L/2ⁿ)²

The total surface area of all particles is

A₍ges₎(n) = N(n) · A₁(n) = 6·L²·2ⁿ

The number of particles thus grows exponentially with the number of crushing steps. The total surface area also increases exponentially, but at a slower rate. For graphical representations, it is therefore useful to use a logarithmic scale for the ordinate.

These geometric and energetic considerations illustrate how strongly comminution processes alter the physical and chemical properties of powders. Medical agents can interact better with biological systems. New high-performance materials are created by sintering the finest powders, for example for applications in electrochemistry, high-temperature technology, superconductivity, optoelectronics, sensor technology, communications technology or energy generation.

The energy required for grinding E is high. It depends on the degree of grinding. Three classic energy laws have been established in grinding technology to describe this relationship.

Rittinger's law assumes that the energy requirement is proportional to the newly formed surface area. It is particularly suitable for fine and ultra-fine grinding. The specific energy requirement is calculated as follows

Eₛ = KR · (1/d₂ − 1/d₁)

- d1: characteristic initial grain size, d2d_2d2: final grain size (e.g. d80 or d50)

- KR: material/process constant

The Kick law describes the energy consumption as a function of the reduction ratio. It is particularly suitable for coarse grinding. Geometric similarity of the particles is assumed. The specific energy consumption is

Eₛ = KK · ln (d₁/d₂)

The Bond law is used for medium grinding degrees. It represents a practical compromise between the two approaches and is often used in the medium crushing range. It takes into account that the energy requirement is related to the square root of the grain size. The specific energy consumption is calculated as

Eₛ = KB · (1/√d₂ − 1/√d₁)

- d1 is the characteristic grain size of the feed material

- d2 is the characteristic grain size of the grinding product

In industrial practice, Bond's law is often used in the form of the Bond Work Index. Characteristic grain sizes such as the 80% pass of the feed F₈₀ and the product P₈₀ are used. The commonly used Bond equation is

Es = 10 · Wi · (1 / √P80 − 1 / √F80)

- F80: particle size at which 80% of the feed is finer

- P80: particle size at which 80% of the product is finer

- Es in kWh/t

- Wi = Bond Work Index (material-specific constant)

- F80, P80 in µm

However, nano-fine powders can also have undesirable effects. Tyre abrasion or micro-plastic particles can pollute the air we breathe and our drinking water. The body's own defence mechanisms can only protect against foreign substances to a limited extent if these are present in nanoparticulate or nanostructured form.