Nickel-based materials

Nickel-based materials are multi-component alloys with a nickel-rich matrix. The most important alloying elements are chromium and molybdenum, which are often supplemented by small amounts of iron, tungsten or niobium. This combination gives the materials a very high level of corrosion resistance to aggressive process media. One such material is Alloy 59. It is a low-carbon nickel-chromium-molybdenum material. Its typical mass fractions are 59 to 63% nickel, 22 to 24% chromium and 15 to 16.5% molybdenum, while the iron and carbon contents are very low.

The material HC22 also belongs to the group of Ni-Cr-Mo alloys. It contains slightly less molybdenum, but additional tungsten, while the nickel content is above 55% and the iron content remains low. Nickel-based materials exhibit very high resistance in chloride-containing media and are highly resistant to both oxidising and reducing acids.

The low carbon content reduces carbide formation at the grain boundaries and thus reduces the tendency to intergranular corrosion after thermal stress. Similar nickel-based alloys are Alloy 625, Alloy 686 and Alloy C-276, with Alloy 625 also containing niobium. This enables precipitation hardening and improves creep resistance and creep strength at elevated temperatures. Alloy C-276 has a very high molybdenum content and often also contains tungsten. This further increases its resistance in highly reducing and contaminated media.

Nickel-based alloys have high mechanical properties. In the solution-annealed state, the yield strengths are typically between 300 and 500 N/mm2. Even at elevated temperatures, a large part of the strength is retained, which distinguishes them significantly from austenitic stainless steels.

These materials are challenging to weld. The chemical composition of the base material and filler material must be carefully matched. Welding consumables are often slightly over-alloyed to compensate for alloy losses and ensure the corrosion resistance of the weld seam. Low heat input, limited interpass temperatures and controlled multi-pass welding are crucial.

Ferritic stainless steels represent a separate group of materials. Their matrix is ferritic, the nickel content is low or completely absent, while the chromium content is usually between 12 and 30%. Compared to austenitic steels, they have lower thermal expansion and higher thermal conductivity. This makes them more dimensionally stable during temperature changes. However, ferritic stainless steels have limited corrosion resistance. In chloride-containing media, pitting and crevice corrosion occur relatively early, while stress corrosion cracking is much less common. Modern ferritic stainless steels are very low in carbon and nitrogen. They are often stabilised with titanium or niobium to control carbide and nitride precipitation.

Ferritic materials such as 1.4509 or 1.4521 are considered economical alternatives for moderately corrosive environments and elevated temperatures. Ferritic stainless steels are sensitive to welding, as grain growth and embrittlement can occur in the heat-affected zone. Controlled heat input, suitable welding sequences and, if necessary, heat treatments are therefore required. Nickel-based materials are preferred for highly aggressive chemical media due to their superior combination of chemical resistance and mechanical safety.

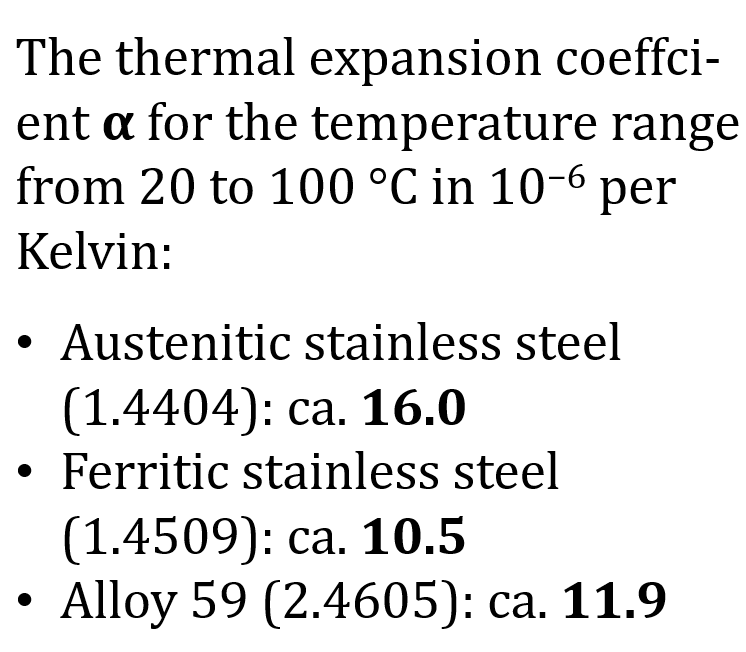

The coefficient of thermal expansion α is temperature-dependent and, in the case of ‘austenitic’ and ‘ferritic’ materials, also depends heavily on the specific grade. The values below are standard comparative values for the specified temperature range of 20 to 100 °C in 10−6 per Kelvin.

- Austenitic stainless steel (e.g. 316L / 1.4404): approx. 16.0

- Ferritic stainless steel (e.g. 1.4509 / 441): approx. 10.0 to 11.0

- Alloy 59 (UNS N06059 / 2.4605): approx. 11.9