Surface activity

The term surface activity describes the ability of a surface to interact with its environment. In particle technology, this primarily refers to the behaviour of particles at their interfaces. As particle size decreases, the proportion of atoms at the surface increases significantly, so that surface effects increasingly dominate over volume effects.

In dry powders, surface activity is predominantly determined by physical forces. Intermolecular and atomic interactions, in particular van der Waals forces, play a central role. These forces are always attractive and are due to fluctuating dipoles. Their significance increases significantly as the particle radius decreases.

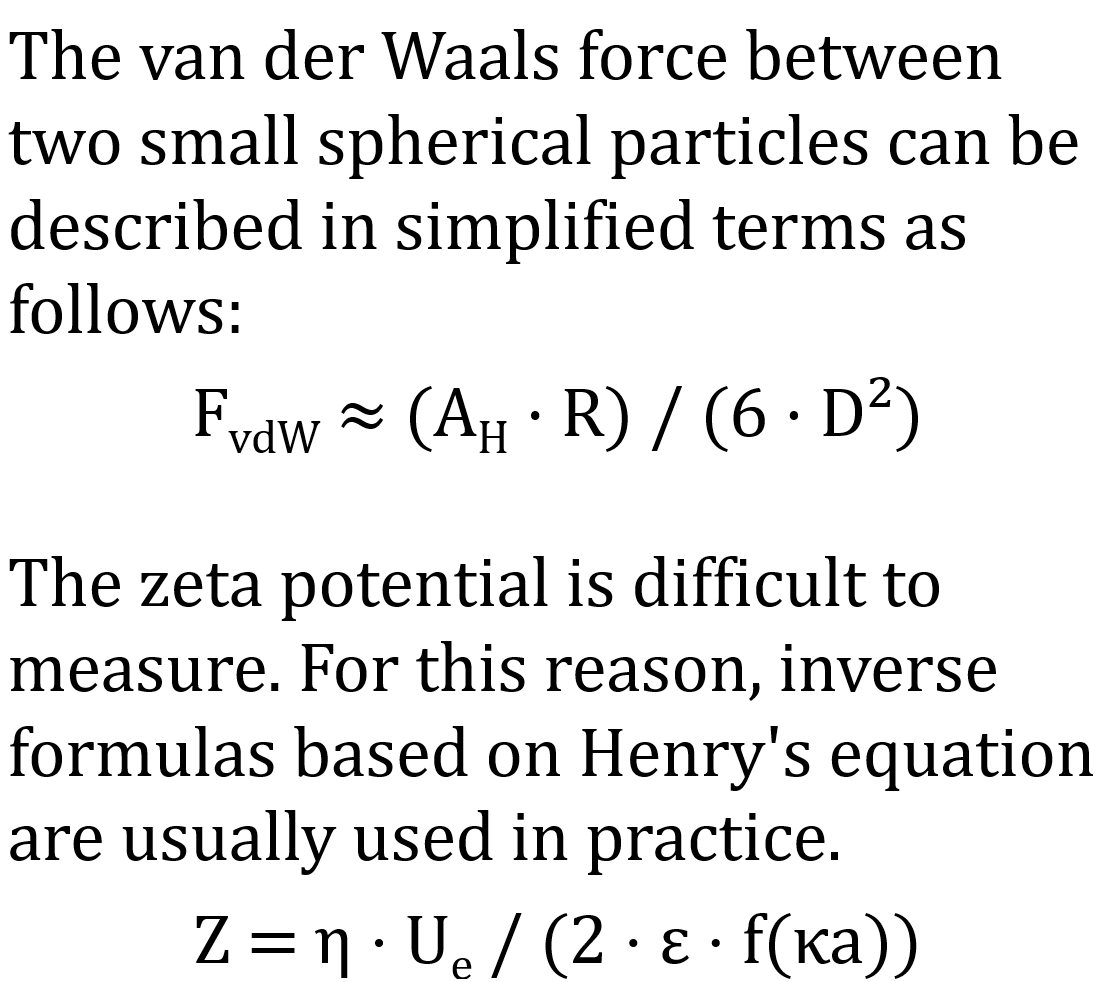

The van der Waals force between two spherical particles can be described in simplified terms as follows:

FvdW ≈ (AH · R) / (6 · D²)

- AH is the Hamaker constant

- R is the particle radius

- D is the distance between the surfaces

As the radius decreases, the ratio of adhesive force to weight force increases. This is why fine powders tend to cohesion. They flow poorly, form agglomerates and adhere to equipment surfaces. In addition to van der Waals forces, electrostatic forces also come into play. These arise from charge separation during mixing, friction or pneumatic conveying. High surface charges can occur, especially with dry, insulating powders. These forces can be attractive or repulsive. They influence segregation, dust explosion risks and adhesion.

Chemical surface activity plays a role in electrochemistry and reactive solids. Reactive functional groups on the particle surface can react with gases or other solids. Examples include oxidation, hydrolysis or adsorption of moisture and gas molecules. Such effects alter the surface energy and thus the flow behaviour.

Optical surface activity is also relevant for powders. It describes the interaction with electromagnetic radiation. The emission and absorption properties depend on surface roughness, colour and chemical composition. This influences heat absorption, infrared radiation and heating behaviour in drying or reaction processes.

In moist powders, the spectrum of surface forces expands. In addition to the dry interactions, capillary forces occur. Liquid bridges form between particles. These bridges generate strong attractive forces and promote agglomeration.

The capillary force can be described in simplified terms as:

Fkap ≈ 2 · π · R · γL · cos(θ)

- R is the particle radius

- γL is the surface tension of the liquid

- θ is the contact angle.

Moist powders therefore often exhibit strong cohesive behaviour. Surface activity increases sharply. Agglomeration, balling and wall adhesion are typical consequences. In process engineering, this effect is exploited specifically, for example in granulation.

In wet powders and suspensions, behaviour is determined by the interfaces between solids and liquids. Electrostatic interactions play a dominant role here. Particle surfaces often carry charges. An electric double layer forms around each particle. The interaction of attractive Van der Waals forces and repulsive electrostatic forces is described by DLVO theory. The resulting interaction potential determines the stability or agglomeration of the suspension. Electrostatic repulsion depends on the zeta potential. High zeta potential values lead to stable suspensions. Low values promote flocculation and sedimentation.

The zeta potential is difficult to measure. For this reason, inverse formulas using Henry's equation are usually used in practice.

Ζ = η ⋅ Ue / (2 ⋅ ε ⋅ f(κa))

The following applies:

- Ue is the electrophoretic mobility of the particle.

- η is the dynamic viscosity of the liquid.

- ε is the dielectric constant (permittivity) of the medium.

- f(κa) is the Henry function, which depends on particle size and Debye length.