Nanodispers

Nanodispers refers to a state in which solid particles are predominantly in the nanometre range. Most technical bulk materials are microdispersed. This means that their particle sizes are typically in the range of a few micrometres. One micrometre corresponds to one millionth of a metre and is written as 10⁻⁶ m. For comparison, a human hair has an average diameter of about 60 micrometres. Powders with micrometre-sized particles are generally easy to handle. They can be conveyed, mixed, filled, poured and, in most cases, reliably dosed. Gravity dominates over the forces acting between the particles.

If the particle size is reduced by a factor of about 1000, the powder is nanodisperse. The characteristic particle dimensions are then in the range below 100 nanometres. In this size range, the physical properties change fundamentally. The flowability decreases significantly. Nanodisperse powders are difficult to pour and dose. They often appear sticky, even when dry.

This is due to the strong increase in interparticle forces. Van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions and capillary effects dominate over the weight of the individual particles. For spherical particles, the weight force FG scales proportionally to the particle diameter d cubed, while the attractive surface forces FA are approximately proportional to the particle diameter. This can be described in simplified terms:

FG ∝ d³ and FA ∝ d

For mixing processes, this means that mechanical energy must primarily be applied to overcome adhesive and agglomeration forces. The shear or impact energy required for agglomerate breakdown increases significantly as particle size decreases. Classic gravity-dominated mixing mechanisms lose their effectiveness. Instead, shear fields, local pressure peaks and wall contacts determine the mixing process.

Nanoparticles adhere strongly to each other and to apparatus surfaces. They have a pronounced tendency to agglomerate. Agglomerate formation is energetically favoured because contact reduces the free surface energy. The driving force can be described by the surface energy:

ΔE ≈ γ·ΔA

γ is the specific surface energy, ΔA is the reduced surface area during agglomeration.

For dust removal and separation processes, the low sedimentation effect of gravity is decisive. The sinking velocity of individual particles approximately follows Stokes' law and is proportional to the square of the particle diameter. In the case of nanoparticles, the sedimentation velocity is extremely low. Thermal motion and air currents dominate.

Separation mechanisms are therefore based less on gravity than on diffusion, electrostatics or filtration. Nanodisperse particles can remain suspended in the air for a very long time. Even the slightest air movements lead to renewed turbulence and dust formation. This places high demands on containment, ventilation and dust extraction systems.

Many nanodisperse dusts are respirable. They can penetrate into the alveoli and are therefore considered potentially harmful to health. The requirements for occupational safety and explosion protection are correspondingly high.

If a solid is present in nanodisperse form, its physical and mechanical behaviour can differ significantly from that of the macroscopic material. Ceramic materials made from nanoparticles, for example, can exhibit increased toughness or apparently ductile behaviour that is not observed in coarse-grained ceramics. Nanodisperse goods enable the development of high-performance materials for electrical engineering, chemistry, aerospace and engineering ceramics. Functional properties can be specifically adjusted via particle size, interfaces and microstructure.

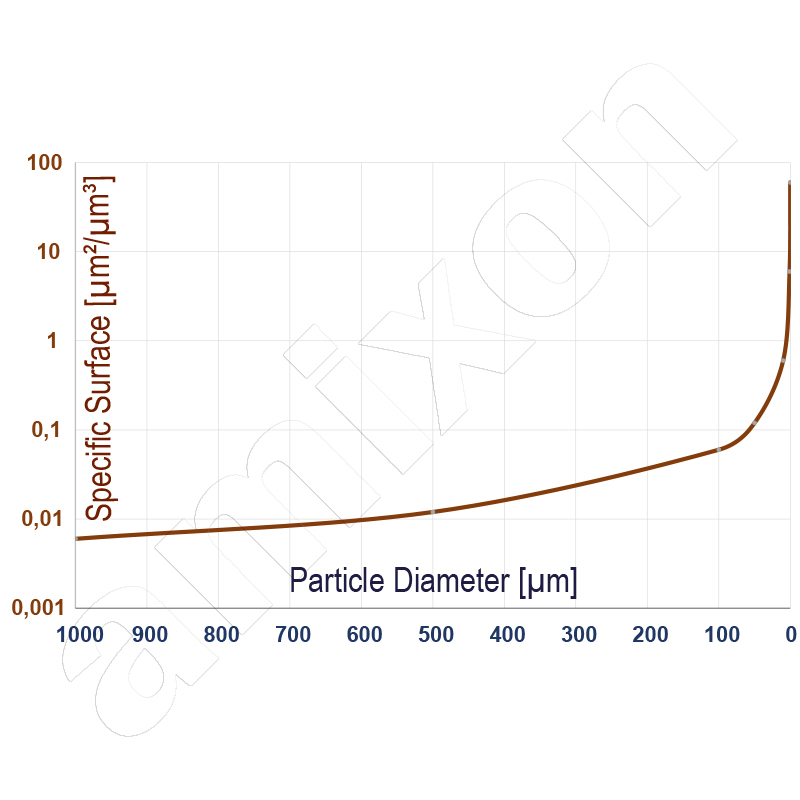

Nanodisperse powders have an extremely large specific surface area As. For spherical particles, it is approximately inversely proportional to the particle diameter d and the density of the solid ρ.

As ≈ 6 / (ρ·d)

The formula is an approximation that applies under the following assumptions: spherical particles, smooth, non-porous surfaces, narrow particle size distribution, no agglomerates, but primary particles. The large surface area leads to high reactivity, increased combustibility and, in extreme cases, dust explosion potential. The dispersion of nanodisperse powders in liquids is particularly challenging. Due to the strong interparticle attractive forces, nanoparticles usually occur as agglomerates. For an agglomerate-free dispersion, these forces must be completely overcome. The required dispersion energy is high and increases with increasing specific surface area. In addition, freshly separated nanoparticles in liquids tend to re-agglomerate immediately unless stabilising mechanisms such as electrostatic repulsion or steric hindrance are at work. A permanently stable, agglomerate-free dispersion therefore usually requires intensive mechanical energy input, suitable dispersing aids or targeted surface modification of the particles.